Goodbye to an Old Friend; the Story of How Camera Boy became a Bestseller

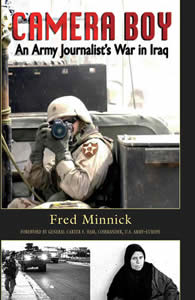

My first book, Camera Boy: An Army Journalist’s War in Iraq, will be going out of print soon. (Buy a copy now before some asshole charges $400 for a used signed copy of an out-of-print book!) It’s a sad goodbye, but an important one as I continue to move my career to writing whiskey history books. As mentioned in my Memorial Day Post, I still do my best to stay in involved with veterans issues. But my career has taken me to a different place–whiskey, of all worlds–and I’m extremely happy where things are going. I’ll always be a veteran, and Camera Boy will always tell that story of my life.

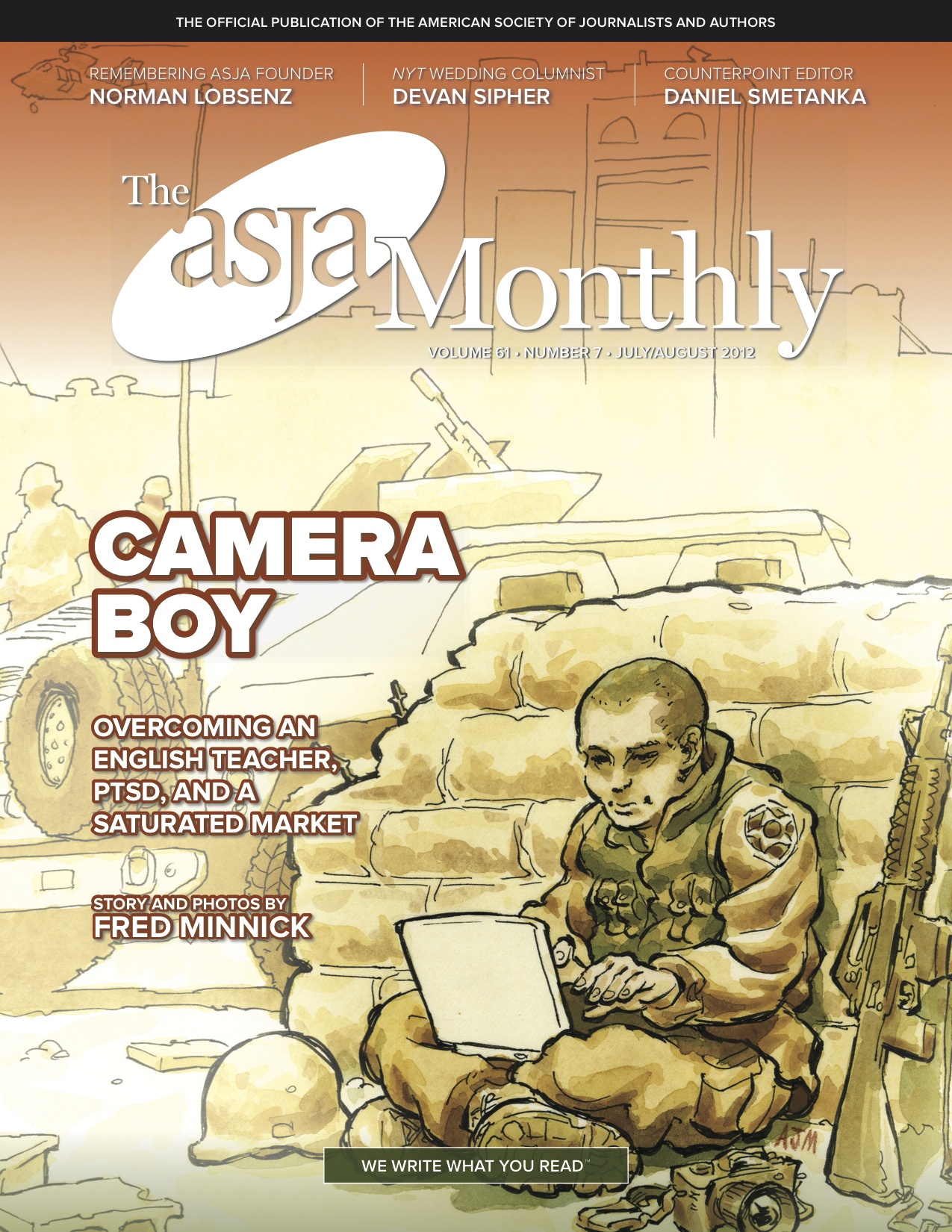

Camera Boy was also my validation for going to war and losing much of my twenties to some moments I still can’t remember (Do I want to remember them?). And the journey to getting Camera Boy published in the first place is one of my all-time favorite stories to tell other writers. The essay below was the July 2012 cover story for ASJA Monthly. I hope it helps another writer pursue his or her dream.

Camera Boy: Overcoming an English Teacher, PTSD and a Saturated Market

By Fred Minnick

Filled with fragments, run-on sentences, misspelled words, and dreadful grammar, my high school essays showed imagination with little structure or proper training. But I was the Jones High School correspondent for the local newspaper and thought I wrote more like Ernest Hemingway than Fred the country boy. My prized hog stories appeared front page of the Oklahoma County News, boosting my 15-year-old ego. My first really tough editor, though, didn’t understand my Hemingway-like fame.

My English teacher held my essay in her cold hands. “Fred, you should become a welder, not a writer,” she said. “This isn’t for you.”

My English teacher held my essay in her cold hands. “Fred, you should become a welder, not a writer,” she said. “This isn’t for you.”

I was not devastated or defeated. I was pissed. I broke important news about Josh Effinger’s Spotted Poland China winning breed champion at the county fair. What did she know about such important journalism works? From that point on, whether I discovered a talent for reading minds or quadratic equations, I channeled every academic fiber to become one of you: a writer making words look good on paper.

This drive gave me the resilience to learn from my professors’ critiques, zero hesitation to interview world leaders, and the confidence to write about any subject I desired. Yet this fire turned to smoldering ash when I was shipped to Iraq in 2004. Bullets, bombs, and bad guys have a funny way of doing that to a fella.

I was an Army journalist and my mission was to tell the Army’s story, but I received more combat photography duties than anything else. Instead of mostly photographing and writing about school openings, I photographed the infantry and Special Forces in action. My camera captured man at his worst: fresh dead bodies, car bomb craters filled with charred body parts, a Mosque’s beheading chambers, and the remains of errant American missiles that destroyed civilian property. The things I saw, and the things I did, not only took my innocence—they ruined my resolve.

My Iraq trauma can be boiled down to one moment—a Russian-made RPG flying toward me. The person pulling the trigger intended to take my life just as we intended to take his. This was war, a form of hell nobody wants to experience . More than 90 percent of the time, the RPG rocket explodes upon impact and kills any living being within 32 feet. I stood there, 10 feet from the RPG’s landing spot, nothing to shield me from the potential blast. I was as good as dead. My life flashed before my eyes. My main thought was about my alma mater, Oklahoma State. I wondered if it would ever win a football championship. Seriously. That’s my last thought?

The rocket hit concrete, bounced over my head and did not explode. Although the firefight continued, the next thing I remember is riding back to the base with people still shooting at us. I can’t remember those ensuing moments; a psychiatrist says the brain remembers when it needs to remember. Whatever happened next, I lived.

That was one of many close calls, but probably the closest. After I returned home, this particular day, June 24, 2004, haunted me and almost destroyed my hopes for a new life. Diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), I chose to fight and not allow myself to become another homeless veteran. I did the only thing I knew how: I wrote about it.

Turns out that writing about pain is called exposure therapy and it’s prescribed in cognitive processing sessions. My words poured out of me unlike anything I had written before. I cried in the middle of sentences, remembering fallen friends, and I laughed out loud, remembering military humor. And throughout all of the writing, I had bouts of sickness, reliving June 24, the near death moment that defined Iraq and words on my laptop screen.

When I completed the 80,000-word manuscript, I tried to sell Camera Boy.

When I completed the 80,000-word manuscript, I tried to sell Camera Boy.

But, like many writers, I did not have a clue about the next step. Now I look back and laugh at those conversations and wonder how I actually got through to New York’s best agents. (I actually called agents and told them about the book!)

After reading my initial draft, all agents rejected it within days.

From agent Mickey Choate: “Thank you for your query letter of November 20, regarding Camera Boy. The market is so saturated with memoirs from the war in Iraq that many of them are having trouble standing out and selling. I’ll have to take a pass. Thanks for thinking of me.”

For the first time in my 26 years, criticism, like my English teacher’s words, cut through my veil of confidence and hit bone. The same toughness that allowed me to deal with the red ink marks on my pages and kept me alive in Iraq was gone. When an agent questioned a verb or an anecdote or gave me the “saturated market” excuse, I wallowed in pity, thinking people were attacking my role as a soldier. These painful rejections made me realize that Camera Boy was more important than my sports copy at The Daily Oklahoman because my attitude has always been edits make the story stronger. But I needed validation for my time in Iraq and a Camera Boy edit felt like an insult to my service with the underlying belief that I gave so much to my country; didn’t anybody want to read about it?

I hired manuscript editor Lary Bloom to make the book more marketable. We trimmed copy and included more details about my job as a photographer. After spending more than 60 hours on the revision, a big time New York agent, Peter Miller, took on Camera Boy.

But all book editors said it wasn’t political enough or anti-media enough. The saturated Iraq book market rewarded those with slants against President Bush or negative views about the media.

Nobody wanted my story.

This craving for validation only added to my PTSD problems. I went to bed each night wondering why nobody wanted the story I had dedicated to my fallen friends.

As is typical with large literary agents, Peter did not want to sell it to smaller firms that would pay on net royalties. My goal was just to get the book sold, and he gave me the okay to try to sell it on my own. Without an agent, I pitched for six months until I couldn’t take another rejection.

Then my friend, Sgt. Ryan Jopek, was killed in Iraq on my birthday in 2006. Much like my English teacher’s negative comments drove me to become a writer, to preserve my friend’s name, I would do everything it took to sell Camera Boy. I began undergoing intense therapy to stop the war from controlling my life and to ease the validation needs I had toward Camera Boy. I didn’t need a book editor’s approval; I gave my country everything I had, and that was that.

But Ryan’s death strengthened my resolve. If it took 30 years, I would sell Camera Boy. At the time, I was a full-time freelancer writing for VFW Magazine, National Guard Magazine and MSN, building my client base to sweeten my platform. I sent 12 queries a week to smaller independent presses. Some publishers requested proposals; others wanted the whole manuscript.

One editor at Lyon’s Press loved the memoir, then picked up a different Iraq book that became a bestseller.

I trudged on, receiving interest from editors only to hear the traditional “market is just saturated” response. I continued editing the book and fellow soldiers read it. I added colorful anecdotes and deleted sections that clunked up the copy. As editors pondered, I was making it tighter, better. I even added a powerful epilogue that included Ryan’s death.

In the summer of 2007, I gave Peter Miller a call wondering if he would give it one more try. Being naïve about publishing, I figured a new chapter might entice a publisher to take a second look. Instead Peter recommended I write another book for two-deal package.

I wrote my college memoir, a book of debauchery, drugs, and booze tentatively titled Frat Boy, which Peter shopped with Camera Boy. I was somewhat glad the publishers not only said no, but hell no; Frat Boy was rushed and filled with stories I did not want to be remembered by.

I continued therapy. Cognitive processing techniques helped free me from haunting Iraq memories. My confidence, my work ethic, and my tenacity were slowly returning. That belief in myself led to more work.

By January 2008, I started bidding on corporate book jobs even though the only book credit I had was two blog posts published in The Blog of War: Front Line of Dispatches of Iraq & Afghanistan (Simon & Schuster, 2006), but I proudly listed on my résumé that I was the author of Camera Boy: An Army Journalist’s War in Iraq. Potential clients respected the fact I was still shopping the book and considered me for corporate books. In May 2008, I signed my first book contract, the biography for Certified Angus Beef.

Afterward, I added this to my Camera Boy pitches and proposal, giving potential Camera Boy editors confidence that I was a serious writer. From the moment I signed Certified Angus Beef, I sent queries every publisher that had ever printed a military book. This time they took longer to review my book, a good sign I hoped, and the rejections contained more details than just the “not right for us” verbiage.

By the fall of 2008, I had a slick website, credits in more than 50 magazines and a better understanding of the book business. That November I followed up on a query from 10 months prior thatI had sent to Hellgate Press, a small military history publisher. The editor took a second look at my query, requested a proposal, then the full manuscript. He said he’d publish Camera Boy if I made some changes, recommendations that only helped the book.

When it sold in January 2009 to Hellgate, I no longer needed America’s approval. I just wanted to keep my many friends’ memories alive. I planned to work my butt off until every copy was sold.

The press run was miniscule compared to Random House’s backlisted titles, but I promoted Camera Boy as if it were to be the next New York Times bestseller. I signed and sold more than 300 books during my five state book tour, landed 42 local and regional press opportunities, and gave speeches to schools and at military events. With every speech, I remembered my fallen friends T., Mitts, Ryan, and my Iraqi friend Samir.

I ignored the negative reviews, which usually came from Army public affairs soldiers who didn’t like how I painted the Army, and I cherished the positive ones. When Camera Boy earned the 19,000th spot on Amazon in December 2009, I felt as if it had just sold a million copies.

Camera Boy was special, my first book in a hopefully long writing career. By 2011, I was accepted into ASJA and was busy publishing articles in top tier magazines, while my Certified Angus Beef book became a must read for every cattle rancher in the country. My promising food, wine and spirits journalism career pulled my attention away from Camera Boy. I figured the book would sell until none were left in print and live on through Kindle and Nook. I was fine with that.

But I never gave up on promoting it and continued to put myself out there for media interviews. I monitored HARO requests for opportunities that related to Iraq or a soldier’s struggles upon returning home. Publicist friends forwarded me ProfNet requests. I sent copies to colleagues I met on press trips. At some point I became known as the wine and whiskey writer who wrote a book about Iraq. Winemakers came to interviews with my book in hand wanting a signature, and wine writers were reviewing of my book on Amazon and their blogs. My active Twitter account of 45,000 followers and the Camera Boy Facebook page continued publishing the book’s Amazon URL. I’d plug Camera Boy in the magazine contributor sections when I could.

These efforts, well after the book’s prime marketing time, led to an interview in Forbes.com, a front page article about my book in Brazil’s most widely read website, g1.globo.com, and a strange cult-like following in the wine world. The book even earned a mention in the prestigious Harvard’s Nieman Foundation’s Nieman Reports (Winter 2011). Suddenly, the career I built outside of Camera Boy helped it to receive the attention I thought it always deserved. I was no longer sending press releases or trying to get time on NPR, but I continued to talk about Camera Boy to anybody who would listen.

Two and a half years after publication on May 2, 2012, Camera Boy became the Amazon Kindle book of the day. Within four days, it sold more than nearly triple the eBooks of my initial print run. The next week Camera Boy earned the No. 10 spot on the Wall Street Journal Best-Selling eBooks. Neither my publisher nor I have the slightest clue how Camera Boy was selected for the Amazon Daily Deal, but the title took off and has been selling ever since.

As I drove home from the doctor’s office, where I learned about making the list, tears rolled down my face. I, Fred Minnick, the country boy who should be a welder, whose book wasn’t appropriate in a saturated market was a best-selling author.

I never gave up on Camera Boy. Not when the rejections piled up. Not when the editors said to write an anti-Bush section. Not when one editor said my book was as good as sold until an Iraq dog book hit his desk. And not when bookstores refused to carry it because they never heard of Hellgate.

In this profession, we receive more no’s than yes’s. In battling PTSD, I learned to treat writing as a business, which loosened my need for validation. Yet I used every rejection as motivation, just as my high school English teacher’s words helped me select a career.

I allowed myself to learn from industry veterans and to not let myself take rejections personal even for a project as close to my heart as Camera Boy. There’s only so much we writers can control in this business. We can choose to let agents’ and editors’ comments bring us down. Or we can let them spur us on. I chose the latter.

My career will no doubt receive more nasty rejections and more bad reviews.

And I don’t know if I’ll ever make it back on any best-seller list.

But I’m sure going to try.